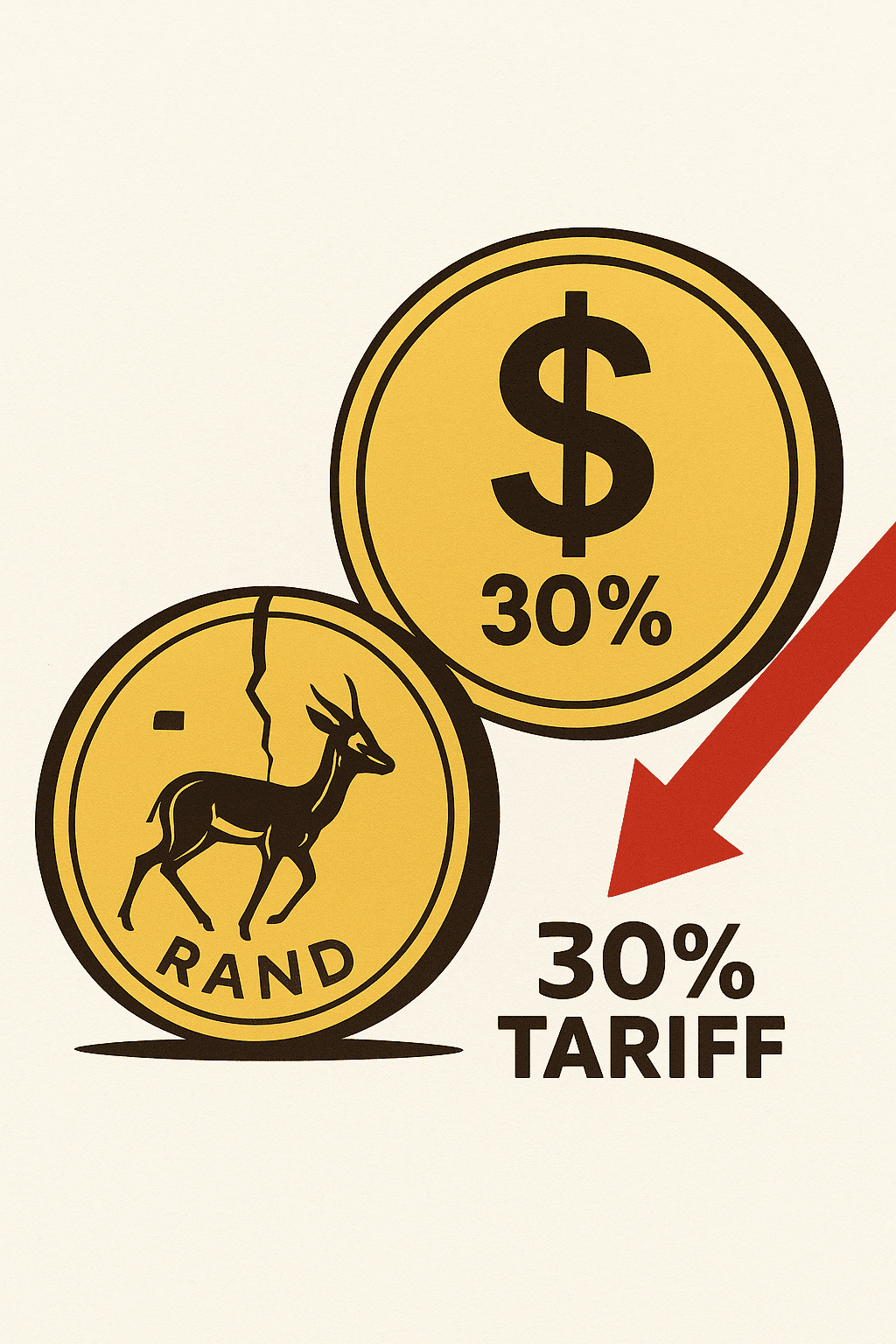

U.S. Tariffs and South Africa’s Jobs Crisis: How a 30% Trade Shock Could Reshape the Economy

U.S. Tariffs and South Africa’s Jobs Crisis: How a 30% Trade Shock Could Reshape the Economy

South Africa is no stranger to economic shocks. From rolling blackouts to currency volatility, the country has learned to live with uncertainty. But the latest challenge — a 30% tariff imposed by the United States on South African goods — is one that threatens not only trade figures but also the very jobs millions of families depend on.

This tariff is more than a line item on a trade sheet. It’s a test of resilience for export-dependent industries such as agriculture, mining, and automotive manufacturing. It’s also a political dilemma for President Cyril Ramaphosa’s government, which now faces the possibility of mass retrenchments at a time when the official unemployment rate already sits at 33.2%.

The question is stark: if South Africa cannot find alternatives, could this tariff shock tip the labour market into an even deeper crisis?

Why the U.S. Matters to South African Exports

The United States is one of South Africa’s most important trading partners, buying billions of rands’ worth of goods each year. From citrus fruit and wine to platinum and vehicles, South African exporters have built decades of trade relationships that help keep factories running and farms profitable.

For many of these industries, the U.S. isn’t just “another market” — it’s the primary market. Citrus producers, for example, rely heavily on American supermarket contracts during the Northern Hemisphere’s off-season. The automotive industry, meanwhile, ships tens of thousands of vehicles and components across the Atlantic each year.

Slapping a 30% price hike on those goods effectively prices them out of the market, leaving buyers to source from competitors like Mexico, Morocco, or Chile. For South African producers, the knock-on effect is immediate: lower orders, shrinking revenue, and looming retrenchments.

Job Losses in Export-Dependent Industries

The most immediate risk is job losses. Export-oriented industries don’t operate in isolation — they anchor entire value chains that employ hundreds of thousands of South Africans.

Agriculture: Citrus, Wine, and Nuts

South Africa is the world’s second-largest citrus exporter, with the U.S. being a prized destination for fresh oranges, lemons, and grapefruits. If American importers walk away, citrus farms — particularly in Limpopo, Mpumalanga, and Eastern Cape — will face surpluses that depress local prices. Farmers may have no choice but to let fruit rot or sell at a loss.

The wine industry is equally vulnerable. Boutique winemakers in the Western Cape often rely on U.S. distributors for premium sales. Without that outlet, jobs in harvesting, bottling, and tourism will be on the line.

Together, agriculture supports over 850,000 jobs, and while not all are tied to U.S. exports, the ripple effects could put tens of thousands of seasonal and permanent workers at risk.

Automotive: The Eastern Cape’s Lifeline

The automotive sector is one of South Africa’s biggest industrial employers, contributing nearly 5% to GDP and sustaining around 500,000 jobs across assembly, components, and dealerships.

Companies like Volkswagen, Mercedes-Benz, Ford, and Isuzu assemble vehicles in South Africa for export. A significant portion of those vehicles are destined for American consumers. If exports slump, these firms may scale back production shifts or mothball certain plants.

For towns like Uitenhage (Kariega) and East London, where automotive factories are lifelines, job losses wouldn’t just be numbers on a spreadsheet. They would mean rising poverty, shuttered small businesses, and declining municipal revenues.

Mining and Minerals

Mining has always been South Africa’s backbone, from gold and platinum to iron ore and manganese. The U.S. market may not be the largest buyer of raw minerals, but it is critical for platinum group metals, which are used in catalytic converters and electronics.

If U.S. buyers shift supply chains, South African miners could face layoffs. Considering the industry employs more than 450,000 people, even a 5% contraction could mean over 20,000 jobs lost — primarily in rural areas with few alternatives.

The Multiplier Effect of Retrenchments

Job losses in these industries don’t stop at the factory gate or farm fence. Each retrenched worker supports, on average, five to six dependents. In many households, a single salary keeps children in school, pays for groceries, and covers transport.

When those wages disappear, the social fallout is enormous:

- Rising poverty in rural and industrial towns

- Greater strain on social grants and government welfare

- Increased risk of unrest, as seen in previous episodes of mass unemployment

South Africa’s already fragile social contract could fray further, especially if young people — who make up the bulk of the unemployed — see little hope of work.

The Rand and Inflation Spiral

The tariff shock has already rattled financial markets. The rand slipped close to 18 ZAR/USD, reflecting investor concern about lost export revenue. A weaker rand makes imports more expensive, which in turn drives up the cost of fuel, food, and machinery.

For ordinary South Africans, this means higher grocery bills, pricier petrol, and rising inflation. Even those not directly employed in export sectors will feel the pinch.

Government’s Dilemma

President Cyril Ramaphosa and his cabinet are under pressure to act. But the options aren’t simple.

- Retaliation with counter-tariffs risks escalating a trade war South Africa cannot win.

- Bailouts for struggling industries would strain an already stretched national budget.

- Quiet diplomacy may buy time, but negotiations could take months, leaving industries in limbo.

The government’s credibility is at stake. For a country already dealing with load shedding, slow growth, and high debt, mishandling this crisis could deepen public discontent.

What Are the Alternatives?

South Africa can’t afford to stand still. If the U.S. market closes, exporters need new doors to open.

Europe

The EU is already a major buyer of South African fruit, wine, and vehicles. Strengthening these ties could soften the U.S. blow, though the EU market is highly regulated and competitive.

Asia (China and India)

China’s appetite for raw materials remains strong, while India represents a fast-growing consumer market. Expanding trade here could offset some U.S. losses, but logistics and price negotiations pose challenges.

Intra-Africa Trade

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) offers new opportunities for regional integration. However, infrastructure bottlenecks, customs delays, and political fragmentation still hinder seamless trade.

Local Market Development

Another option is to pivot inward — encouraging South Africans to consume more locally produced goods. While this won’t fully replace U.S. demand, it could cushion the impact and create homegrown resilience.

Industry Case Studies

Citrus Exports

South Africa exports nearly 60% of its citrus harvest. The U.S. accounts for about 10% of that. Losing even part of this market could leave thousands of seasonal workers without jobs in peak harvest months.

Automotive Exports

In 2024, South Africa exported over 300,000 vehicles, with thousands bound for American showrooms. If tariffs persist, global automakers may reconsider their South African operations altogether, opting for tariff-free hubs in Mexico or Asia.

Platinum Group Metals

Platinum is a key input for catalytic converters, used in American vehicles. If U.S. demand shifts, miners in Rustenburg and Limpopo could see layoffs. Given mining’s labour intensity, even small demand changes can trigger mass retrenchments.

Long-Term Lessons for South Africa

While the tariff shock is painful, it also highlights deeper vulnerabilities in South Africa’s economic model. For too long, the country has relied on:

- Raw material exports instead of value-added goods

- A handful of key markets instead of diversified partners

- Fragile industries that are exposed to geopolitical winds

This crisis could serve as a turning point. By investing in manufacturing competitiveness, regional trade, and renewable energy-driven industrial growth, South Africa can build a more resilient export base.

Crisis or Catalyst?

The 30% U.S. tariff on South African goods is more than a trade dispute. It’s a wake-up call that exposes the country’s vulnerabilities — from over-reliance on a few export markets to its dangerously high unemployment rate.

If South Africa fails to adapt, the outcome could be devastating: mass retrenchments, social unrest, and deeper economic stagnation. But if it seizes the moment to diversify exports, strengthen local industries, and negotiate smartly, the country could emerge stronger.

The next few months will be decisive. For the workers in factories, on farms, and in mines, the stakes couldn’t be higher. For policymakers, the question is whether this moment becomes another lost opportunity — or the beginning of a more sustainable trade future.