What R350 Grant Recipients Teach Us About Micro-Economies and Informal Trade in South Africa

What R350 Grant Recipients Teach Us About Micro-Economies and Informal Trade in South Africa

In a country grappling with record-high unemployment and deep inequality, South Africa’s R350 Social Relief of Distress (SRD) grant — a lifeline for over 8 million recipients — has become more than just a survival mechanism. It’s quietly fuelling a network of micro-economies and informal trade in townships and rural areas.

While critics have questioned its affordability and long-term value, the SRD grant is reshaping township commerce, supporting hyper-local trade, and showing how even modest cash injections can catalyse economic resilience.

Beyond Survival: The Economics of the R350 grant

First introduced in May 2020 as a pandemic response, the R350 grant now reaches over 8.4 million unemployed individuals monthly, according to the Department of Social Development and SASSA. That’s more than 20% of working-age adults in South Africa relying on R350 to meet basic needs.

The R350 grant has thus emerged as a pivotal element in understanding the economic dynamics at play in these communities.

This highlights the critical role the R350 grant plays in enhancing economic stability.

Yet surprisingly, many recipients aren’t just spending their grants on immediate survival. New data from research institutions like the University of Johannesburg’s Centre for Social Development in Africa (CSDA) shows how this money flows through the informal economy — creating opportunities far beyond the initial payout.

Micro-Transactions Driving Township Economies

For every R350 distributed, there’s a ripple effect:

Spaza Shops see consistent increases in foot traffic on grant payment days. Owners stock up in advance, knowing demand will spike.

Street Vendors selling pap, meat, vetkoek, or second-hand clothing benefit from the short-term liquidity injection.

Hair salons, barbers, and mobile phone repair kiosks also experience small but noticeable upticks in revenue.

One study estimates that each R350 grant circulates up to three times within a local community before it exits into formal retail or services. In practice, this means the R350 fuels hundreds of thousands of micro-transactions across South Africa’s underbanked areas each month.

How Township Trade Adapts to SRD Behaviour

Businesses in townships have adapted around grant patterns. In places like Soweto, Khayelitsha, Tembisa, and Mamelodi:

Flexible Pricing & Stocking: Vendors reduce prices or bundle products near payment days.

Product Matching: Items like 2kg maize meal, mobile airtime, or baby formula are tailored to R350 budgets.

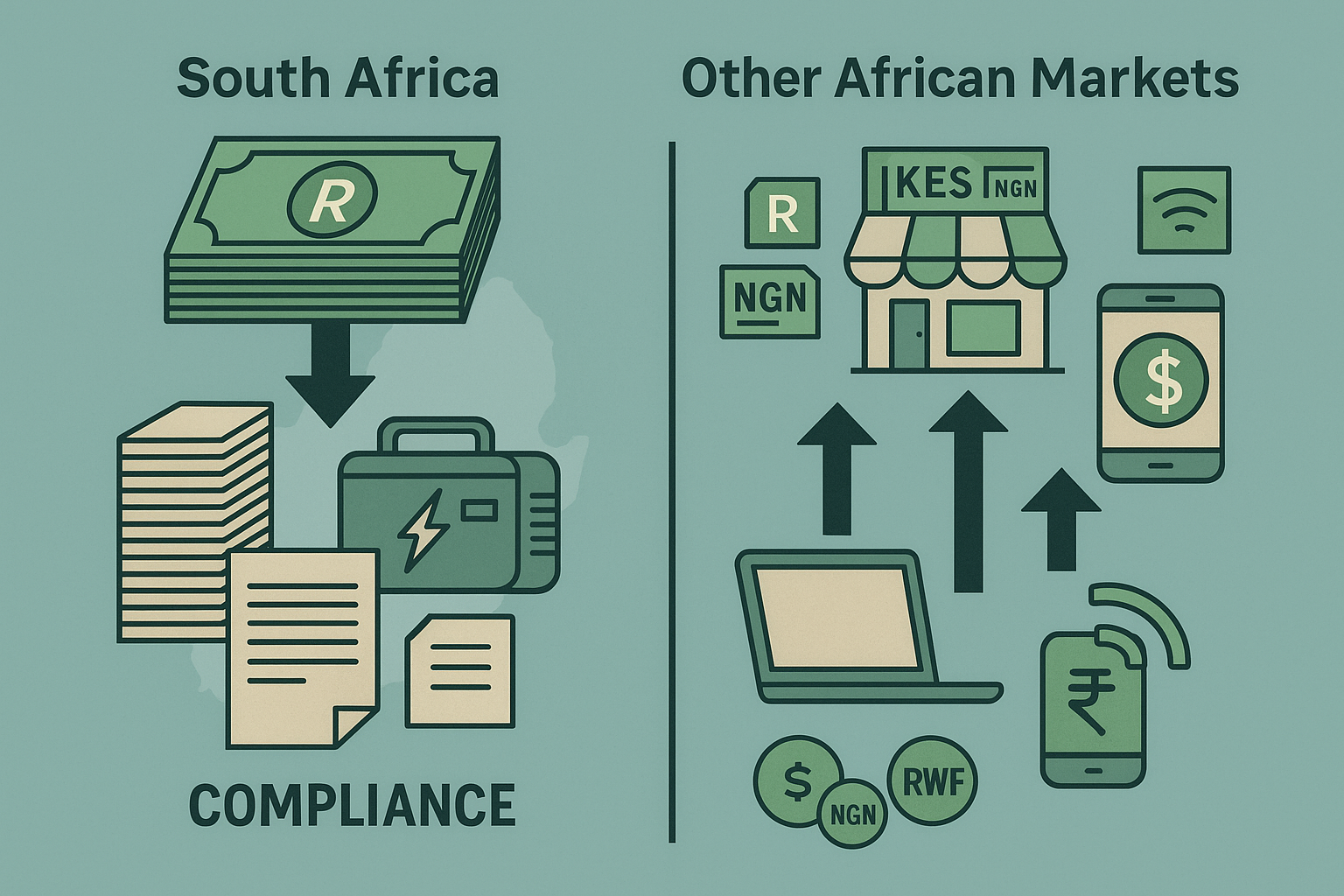

Mobile Money: Increasing use of e-wallets and mobile apps like Shoprite Money Market and Capitec Pay is streamlining grant spending.

While formal banks and major retailers dominate discussions around fintech in SA, it’s informal cash economies that are innovating fastest in response to SRD behaviour.

Who Are the “SRD Entrepreneurs”?

In many communities, the grant doesn’t just feed families — it sparks entrepreneurship.

Informal businesses started or sustained by SRD recipients include:

Reselling cigarettes, snacks, or airtime bought in bulk

Offering home-cooked meals during lunch hours

Hosting informal childcare services for working neighbours

Low-cost delivery services using bicycles or scooters

While none of these ventures make recipients wealthy, they reduce dependency and often serve as the foundation for longer-term survival.

Economic Lessons from the SRD Grant

The existence and spending of the R350 grant reveal deeper truths about South Africa’s economy:

Cash Enables Agency: Even small amounts of reliable income allow recipients to participate in and shape their local economies.

Informal Trade is Essential: According to Stats SA, the informal sector contributes over 6% to GDP and employs nearly 3 million people — many indirectly supported by grant-driven demand.

Dependency Isn’t the Whole Story: Recipients don’t hoard grants. They spend strategically — often investing in community trade and relationships.

Micro-Economies Are Real: In areas where no banks, ATMs, or jobs exist, the SRD grant functions as a mini-currency, activating trade where formal capital does not reach.

Policy Blind Spots: Are We Undervaluing the Informal Economy?

Current economic policy underestimates the power of low-income grants to sustain entrepreneurship. For example:

- NEDLAC and Treasury discussions often frame the SRD as a fiscal burden, not a developmental catalyst.

- Formal business incentives rarely target informal entrepreneurs — even though they drive township spending.

- ESD (Enterprise Supplier Development) policies in big corporates bypass micro-enterprises entirely.

If the SRD grant is treated only as welfare, the government misses an opportunity to design community-level development strategies based on what’s already working.

Where to Next: Should the SRD Become a Basic Income?

There’s growing debate over whether the R350 grant should evolve into a Universal Basic Income Grant (UBIG). Proponents argue that:

It would create predictable local demand, especially in underdeveloped provinces.

It can be paired with digital payment systems to promote fintech growth.

It supports homegrown business development in areas where formal job creation is slow.

Critics cite the cost (estimated at R200 billion annually), but overlook the compounding economic effects observed in local informal ecosystems.

Don’t Underestimate the R350

South Africa’s informal economy has always adapted under pressure. The R350 SRD grant isn’t a handout — it’s become the foundation of township trade, informal entrepreneurship, and family resilience.

From spaza shops to pop-up car washes, from street food to mobile services, the grant teaches us that even modest government intervention can nurture local business in ways no corporate programme ever could.

In an economy as unequal and informal as South Africa’s, the R350 grant isn’t just poverty relief — it’s proof that micro-economies can thrive when dignity meets agency.